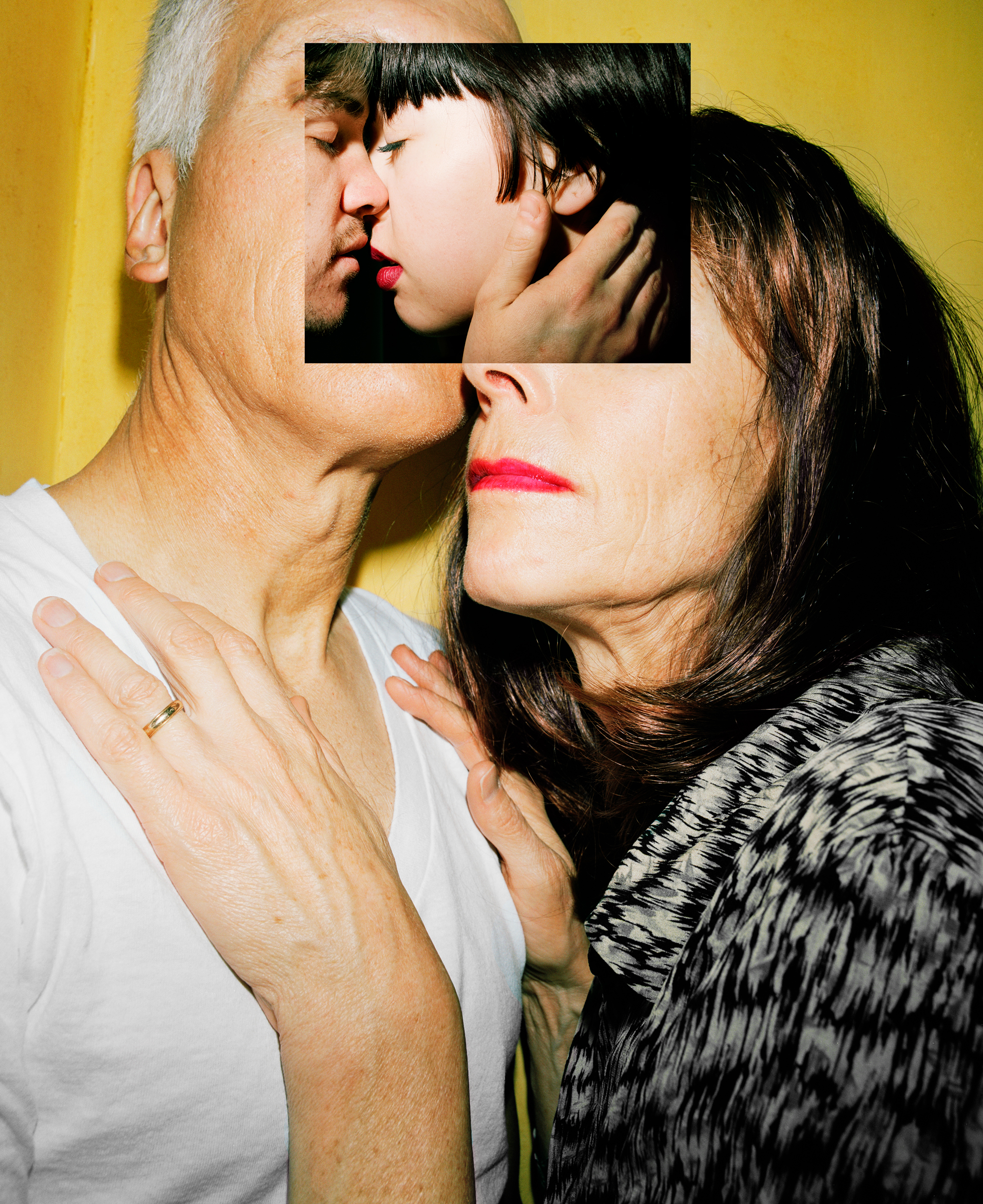

My mother, my sister and I perform for each other, for the camera and ultimately for you. In the harsh revealing light of the flash; we pose, we masquerade until our unstable identities begin to merge. We impersonate each other and ourselves, emulating imagery that has taught us how to be beautiful. The resulting pictures, portraits and fragmented photographs of our stylized bodies, mimic the alluring glamour and artifice found in magazines while mocking the idea of being easy on the eyes. In the act of embodying these tropes, cultural cliches become personal, pointing to the way photography influences the fantasies and fictions we have created about ourselves.

//

How do we learn, as girls and as women both young and aging, to inhabit our bodies? It can seem to be an exercise in self-deception and accidental and occasionally abject revelation, by turns. The twin poles that we travel between, in this ongoing calibration of physical self and inner self, are the images of others—most especially the others who beam at us from the pages of magazines or movie screens—and our mothers. Natalie Krick’s series Natural Deceptions, made in collaboration with her mother and her sister, explores the temptations and degradations that can be found across this spectrum. The images are colorful, witty, aggressively slick—they would feel equally at home as fashion campaign or celebrity portraiture, save for their bite and personal inflection. “My mother, my sister, and I perform for each other, for the camera, and ultimately, for you,” says Krick. “We impersonate each other and ourselves, emulating imagery that has taught us to be beautiful.” An image like Me posing as Mom posing as Marilyn asks the viewer to see the subject through multiple internal filters—the double masquerade implied by the caption and the iconicity of the known image referenced obliquely. Me posing as Mom posing…, like many others in Natural Deceptions, is bistable, or even multi-stable. It functions similarly to any one of those common perceptual tests or optical illusions—“Duck/Rabbit” or “Old Lady/Young Lady” (also known as “Young Girl/Mother-in-Law” or even, more cruelly, “Young Lady/Old Hag”). These images challenge the viewer to hone in on one image over another, but the other identities continue to flicker in the background, informing and influencing the read of the whole. Similarly, we see ourselves in the two-dimensional place of a photograph, but sometimes, we don’t or can’t—we get caught between the layers of self; of destiny as defined by heredity and family resemblances; of projections of what we want to see. Faux thigh gap functions similarly—we see what we have been trained to see, until we snap back to seeing what’s actually in the image: namely an optical allusion to the rampant (and often obvious) photoshopping of women’s bodies so that they might conform to some societally prescribed ideal.

Each of Krick’s images—and at the core of this series—is an effort to puzzle out the nature of photography in relation to feminine identity and selfhood. The image can be adulatory, and it can be savage. In Krick and her co-conspirators’ hands, it is also always compelling.

-Lesley A. Martin